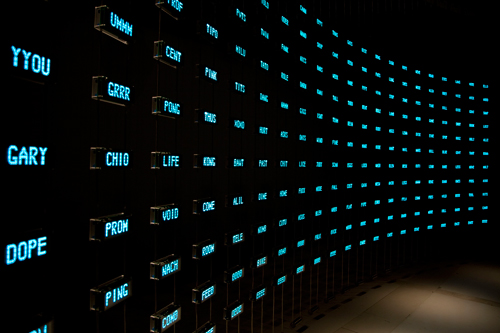

The Listening Post

The Listening Post by Ben Rubin and Mark Hanson is an installation composed of 231 electronic displays (11 by 21) set into a grid onto a curved wall. However, it is primarily a sonic piece. It is a real-time visualization of thousands of ongoing online conversations. The screens display random words picked from these conversation, and these words are being told by a text-to-speech program as they change, all overlapping and creating strange harmonies. With each changing word comes a clicking sound, adding to the piece’s sonic landscape. A last layer of sampled sounds and dreamy musical compositions match the action of the screens.

Ben Rubin explains that he sees this piece as collaborative storytelling that people engage in without being aware of it:

“When I watch the piece, it tends to get my imagination going, because you see these fragments of text and they’re positioned next to each other as if they were in conversation or telling a story but you don’t really know what the context was that these were plopped out of” (Rubin & Hansen, 2013). One emotionally-affecting movement filters for phrases beginning “I am” or “I like” or “I love”. Sample phrases might be “I am in Chicago” or “I am really tired of this election season.” Rubin offered an example, “‘I am stuck again here.’ Someone says something like that, and you wonder, Who are they? And where are they stuck? And why are they stuck again? To me, it’s about where my imagination goes in trying to construct what the context for some of these disembodied statements might be”

(http://modes.io/listening-post-ten-years-on/)

The piece then sends its audience cues of fragmented, separated stories, that people can wonder about, or try and make sense of, using their imagination. This piece is also about people trying to connect through artificial means, as sentences are pulled from chat rooms, online forums, newsgroups and bulletin boards. Or, as Rubin explains:

“There are an untold number of souls out there just dying to connect, and we want to convey that yearning. I hope people come away from this feeling the scale and immensity of human communication” (Mirapaul, 2001).

The piece is also about surveillance, privacy rights, and data malleability. It shows how our online activity is basically public, and available for virtually anyone to use for any purpose. This online life and activity, which is mechanically compiled into sets of data, in which individuality and personality both get lost in translation. The piece also points at the political implication of compiling and using these sets of data, as this data ultimately contains personal stories that were not always meant to be shared with the world as they were created, or written. Hansen and Rubin explain it this way:

“As we become more adept at observing, measuring, and recording both our physical and virtual movements, we can expect to see a proliferation of large, complex data sets. These new digital records of human activity often force us to consider difficult societal questions. From the current debate over privacy on the Internet to ethical concerns over the use of genetic information, we recognize that the now simple act of compiling data has serious political implications. To further complicate matters, the scale and structure of these data make them difficult to comprehend in the large, relegating activities like data analysis to a select few (Hansen & Rubin, 2000)”.

The Listening Post has a strong relevance both within the new media art field and its practices, as well as our surveillance, data-driven society. It has offered an innovative way of including real-time data into art for the time at which it was conceived (2001) and has been greatly influential to the new-media art field dealing with data visualization and sonification. For their ground-breaking use of real-time data, Rubin and Hansen have been cited in many academic and artistic follow-on studies and projects. Wes Modes goes as far as saying that “this piece is hailed as a new media masterpiece” (http://modes.io/listening-post-ten-years-on/). The installation also came out at a time in which gathering of online personal data and its political implications was a very hot topic. The piece is still - if not more - relevant in this aspect as time goes by because online privacy rights have been a growing subject of controversy since 2001. As Modes puts it, “this (online privacy rights) has become ever more politicized since September 11th 2001, the PATRIOT Acts I and II, domestic spying, blanket wiretaps, FISA court abuses, recent NSA revelations, and so many government and corporate privacy abuses the media seem to have grown weary of dragging out George Orwell.” (http://modes.io/listening-post-ten-years-on/). The Listening Post merely relays these raw words and leaves to the audience the opportunity to use it as a conceptual base from which each individual can ask themselves whatever question is sparked in their mind. Do I care about my online privacy? Do I like that the Internet is a somewhat supervised and public virtual place, or should no one be allowed to look into it? Who is watching me, and why? Can this impact my “real” life, and if so, how?

Another artist who dealt with the theme of surveillance in his work is Steve Mann. He coined the term “sousveillance”, which can be understood as “under-surveillance”. Unlike the Listening Post’s omniscient surveillance system, it breaks away from the idea of being watched from above and proposes a surveillance that is brought down to human level, both physically by bringing the surveillance tools down onto people rather than onto buildings, satellites or drones, as well as hierarchically: everyday people are doing the watching rather than it being only done by authorities. People are not being watched by an omniscient entity, like Rubin and Hanson suggest, but rather here Mann offers surveillance as an organic process in which all members of society engage in. From this concept, Mann came up with the Invisibility/Aposematic Suit. The suit has two screens on the front and back of the person. It can become transparent by showing what is behind the user, or “reflective” and show people in front of it a reflection of themselves. It hints at the ways surveillance can be stealthy, or on the contrary made completely obvious in order to let people know they are being observed and deter them from any wrongdoing. Another difference from the Listening post is that it shifts the concept of surveillance from an automated program, or computer which works on a systematic algorithm, to a more human surveillance in which choices are made by individuals, coining in the idea of individuals’ agency and subjectivity in surveillance.

Steve Mann’s Invisibility/Aposematic Suit, 2001

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sousveillance#/media/File:AposematicJacket.jpg

Another artist, James Bridle, has also dealt with surveillance in his piece called The Nor (2014). The work, made in the most surveilled city in the world (London), aims at photographing and listing all of the thousands of CCTV cameras spread around the city. By doing this, he addresses themes such as paranoia and infrastructure within societies of surveillance. In a way, he is turning the tables around and imposing a way of surveillance onto the tools used for citizens surveillance. In this way, this project differs from the two previously mentioned ones, which offer alternative surveillance tools without taking an explicit stand against the whole idea of being under surveillance (but rather aim at audience’s reflexion onto the topic). Interestingly enough, police officers stopped him as he was doing this work, and explained that “carrying a camera was "grounds for suspicion" and he was told he'd be arrested if he didn't identify himself and explain his actions.” (http://mashable.com/2014/11/20/london-cctv-cameras/#ly7tWuHv5PqU)

James Bridle, The Nor (2014)

The Listening Post was shown at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2001, the London Science Museum in 2007, the NY Times building in 2011, and toured in 2013 from the permanent collection of the San Jose Museum of Art to Montpellier, France.