Dys4ia

“Telling us something, anything. Making me feel a connection. Not wasting people’s time, like an eighty-hour blockbuster game that’s all filler. I want people to realize that a game can be a way to share an idea, not to rob them of time and money. To help us understand each other a little better instead of pushing us apart.”

–Anna Anthropy, 2012. Anna Anthropy: Games Should Share an Idea, Not Rob Us of Time and Money

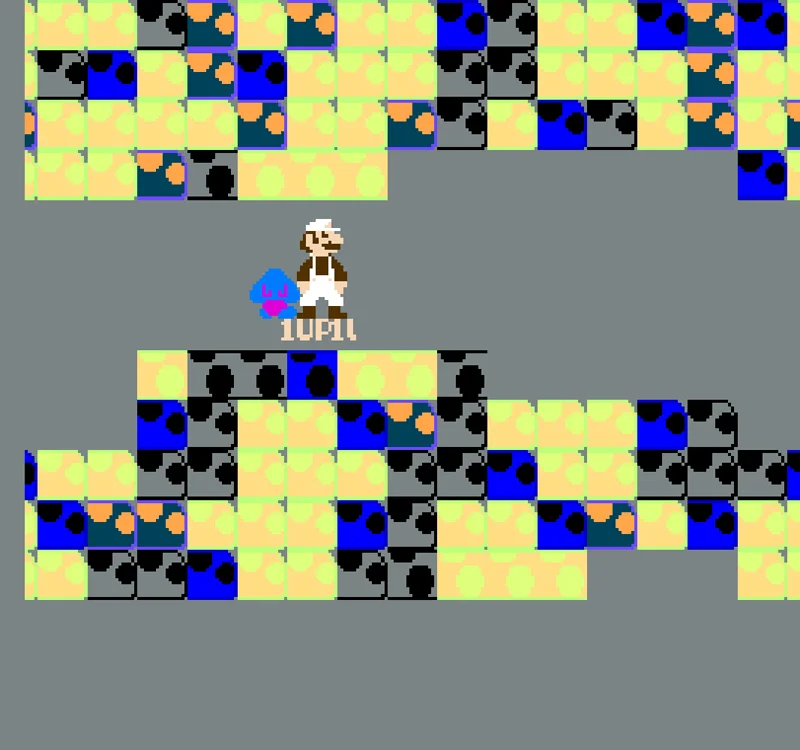

Dys4ia, a game created by Anna Anthropy in 2012, is a short autobiographical piece about gender dysphoria. Instead of creating a challenging or complex gameplay experience, the entire game is played through using simple arrow key gestures and follows a definitive, unalterable storyline. As is typical with the majority of her games, she uses a classic 8-bit style in tandem with an electric color-scheme to create the visual appearance of the game. As for gameplay, it forces the player to go through her personal experience with hormone therapy through a series of quick mini-games. It is broken into four levels, respectively labeled “Gender Bullshit”, “Medical Bullshit”, “Hormonal Bullshit”, and “It Gets Better?” Each one takes you through her deeply personal experience of being a trans woman, giving you glimpses into that experience through mini-games where you have to shave off your mustache or walk down the street as NPCs address you as “sir”.

The experience not only acts as a personal diary, but an experience to be shared with other people, trans and non-transgendered alike. In this sense, it serves two purposes; it acts as a way of supporting other members of the trans community going through similar experiences, and as a way of conveying the struggles of transgendered individuals to the greater population in a way that creates empathy, not sympathy. This is evident from a statement Anthropy made,

“a lot of trans or gender dysphoric people have contacted me and said that it made them feel less scared about going on hormones, or gave them some kind of comfort in shouldering through their own situations, or just let them laugh at a painful part of their histories” (Anthropy, Anna. 2012. Anna Anthropy: Games Should Share an Idea, Not Rob Us of Time and Money).

On the flip side of the coin, there is the experience of a self-identified upper-class, straight, Christian male:

“By the time the 15-minute experience was over, I was closer to understanding the ‘T’ in LGBT than ever before. And not just from a factual standpoint. I understood the feeling. It’s one that many of us can relate to: being misunderstood, outcast, and consequently frustrated by everyone else’s inability to connect and relate. No matter how ‘normal’ you are, we all have felt that at some point. But gender dysphoria goes beyond that. It’s about feeling uncomfortable in your own skin, feeling on a deeper level that what’s inside doesn’t match what’s outside. The opening mini-game of an oddly-shaped block having to fit through a space that just can’t quite be navigated – and then forcing you to try in vain – immediately pushed me into the mindset experienced by transgendered people. It’s a deep-down feeling that ‘this doesn’t work’ – or, perhaps, ‘I don’t work’ or ‘I’m broken.’” (Gann, Patrick. 2012. Playing at Empathy: Anna Anthropy’s Dys4ia)

The experience capitalizes on the humanness of the player. The forced discomfort of the gameplay experience creates a window into her life that could not be achieved in another artistic format. It uses the related feelings and experiences of the player, and attaches them to her own experience, creating the feeling of empathy that the piece evokes.

Anna Anthropy has a tendency to tell a part of her own personal story in every piece she creates. While none of her other games are 100% congruent to Dys4ia, queers in love at the end of the world (2013) comes fairly close. Produced a year after, it’s a Twine game that gives the player only 10 seconds until the world ends, and in that space they must decide their last actions and words with their queer lover. This results in the same fragmented, quick gameplay as Dys4ia, opting for strong impressions and feelings over complicated or challenging gameplay. This game specifically evokes a sense of frustration, which also permeates the storyline of Dys4ia. In terms of subject matter, they both stem from a very personal place and deal with matters of the LGBTQ community.

Another game that aligns well with Dys4ia (but for a different set of reasons) is Never Alone (Kisima Ingitchuna). While the visual styles don’t measure up in the slightest, the purpose of both games is almost identical. They both give a voice to a marginalized, historically oppressed societal group through storyline gameplay. They are both meant as a way of artistically expressing the culture of two groups that have experienced a great deal of suffering, the Inuit Natives in the case of Never Alone and the transgendered community in the case of Dys4ia. Both of these examples act as proof that a game can accomplish more than just entertainment, it can convey a social and political statement.

Other Resources:

Play Dys4ia at- http://jayisgames.com/games/dys4ia/

Interview Transcript on Games for Change- http://www.gamesforchange.org/2012/03/anna-anthropy-interview

Molleindustria’s Review- http://www.molleindustria.org/blog/molleindustrias-top-games-of-2012/