The Long Count

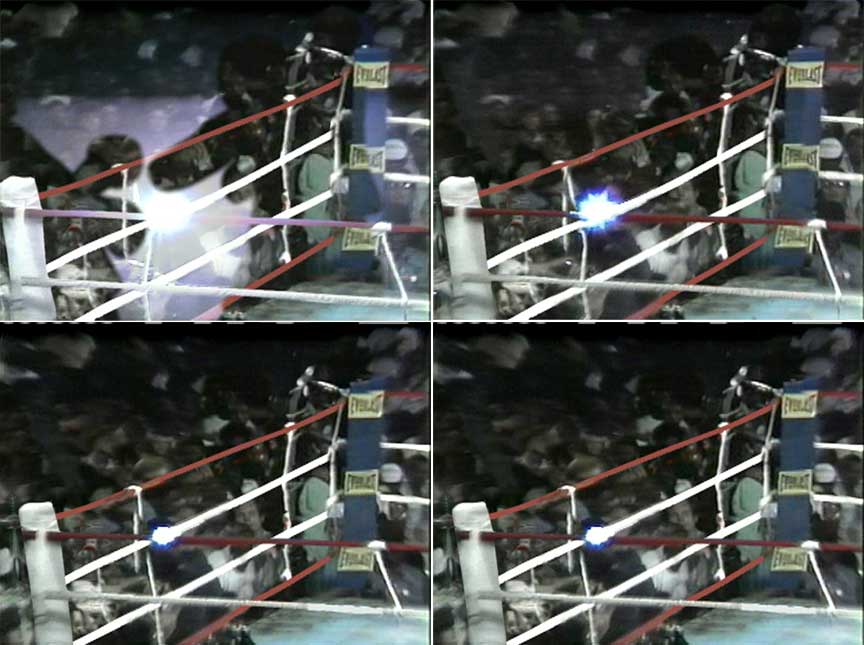

This video piece, made by Paul Pfeiffer in 2001, shows a fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, from which the two fighters have been digitally removed. The footage used is the actual TV broadcast of the event, therefore the piece uses the traditional angle and distance from the fight that viewers are used to seeing while watching boxing matches on TV. The viewer can see and hear the crowd react to the fight, but the two fighters have been digitally “erased” and are leaving visual imprints onto the film that resemble shadow-like ghostly figures.

In The Long Count, and other similar video pieces, Pfeiffer explores the relationship between images, objects and people through the concept of time. Pfeiffer explains that there is something very seductive about pre-digested images, and the huge amount of content that is offered to their audience. By removing the expected focal point, or main subject matter of these videos, Pfeiffer plays with the viewers’ perception of such sports events, and teases our expectations that come from the way we are preconditioned into interpreting the footage of such pre-constructed events. The viewers are being shown an empty ring and a crowd cheering to what seems to be a non-event. However, our massive exposure to such pre-digested images, what they denote but also connote without the need for literal depiction, and the way these associations are deeply embedded in our culture-induced subconscious allow us to infer the “erased” subject matter and its visual non-representation becomes secondary when it comes to making sense of the images shown. By highlighting these automatic associations we make, Pfeiffer is showing the relationship between single images and their structures or network, and how these two are in fact hard to dissociate. In other words, Pfeiffer is asking through this piece who is using who, or is it images that make us or us making images? In our technology and media-driven world, we are no longer making content onto which we have full control. Rather, people and their media influence each other in a symbiotic way. People create media content, which influence their subconscious and eventually the way they create media content. Pfeiffer aims at revealing this synergy through his work and altering of pre-recorded and pre-constructed footage, and this how, in his own terms, he is a “poacher, translator and mediator rather than an author”. Another possible interpretation of this work could be that it is an inquiry into our perception of reality through time, and how, in our visual culture, seeing is believing.

Jennifer Gonzalez, from Bomb Magazine, proposes that Pfeiffer

“used digital editing to address the question of historical visibility or invisibility, emphasizing the power of image culture to confer the status of the “real” onto the past or onto human bodies in the present” (http://bombmagazine.org/article/2543/paul-pfeiffer).

In other words, this piece would be playing with the assumption that something has really happened if there is a visual recorded trace of it. However, Pfeiffer shows that footage of an event can constitute a proof of its veracity even when the important subject matter is removed from it, as our cultural and sensorial conditioning is sufficient for the viewers to accurately guess it from its context. Another interpretation of the work by the New York times proposes this piece as a social commentary on race:

“The deletion of the two black athletes suggests that they are anonymous and expendable players in a centuries-old ritual; the faces that remain are predominantly white, and their avidity, spectatorship and even blood lust seems to be the focus of the work. But the faces might also be the cast-out, watching the forces of good and evil battle for their souls.” (http://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/15/arts/art-in-review-paul-pfeiffer.html)

This view, however, was not echoed by Pfeiffer who is more interested in the technical aspect of the video, and the people to structure relationship explained above:

"What I’m really interested in is where the medium fails, so that what you are seeing is the point at which the erasure can’t happen seamlessly. If the editing was done perfectly, then you wouldn’t see where the figure was at all, but in ‘The Long Count’ triptych you always do. There’s always this trace of where the figure was, and in a way you’re seeing the failure of my hand and the failure of the medium, and that’s kind of the ghost that’s left. And it’s that point of failure that I’m really interested in.” (http://www.pbs.org/art21/images/paul-pfeiffer/the-long-count-rumble-in-the-jungle-details-2001?slideshow=1)

Another video piece by Pfeiffer which uses the same technique is Fragment of a Crucifixion.

Paul Pfeiffer - Fragment of a Crucifixion

(http://www.artnet.com/Magazine/features/saltz/saltz3-29-10.asp)

This piece is a short video loop of a player celebrating a dunk. Pfeiffer explains that, within mass audience spectacles such as sports, there is something inherently compelling about loops. They draw viewers in over and over, like moths to a flame, that can’t help but stare at it.

Fragment of Crucifixion is named after a painting by Francis Bacon from 1950. It depicts a player screaming, but Pfeiffer stripped him from all context (other players around him), making the viewer wonder what he is screaming about. The player is surrounded sensorially by an intense, extreme situation (NBA game) and watched by thousands of people. He is at the center of attention. The implication of this is a sense of his figure dissolving in the accumulation of capital until it becomes an image. The player probably just made a lot of money yet he seems to be in a very precarious situation: he is facing humiliation in the process of becoming only an object of admiration, in a setting in which people are reduced to a product - consumer relationship.

The Long Count is actually an iteration of Fragment of a Crucifixion. It was born from Fragment of a Crucifixion’s technical shortcomings. Pfeiffer tried to achieve seamlessness but one of the figures could not be completely erased, leaving a shadow-like figure which constituted a visual evidence of erasure. The Long Count capitalizes on this quality. This is an instance of times when things that will happen against your will end up being more interesting than what was first intended.

Another artist who plays with the relationship between visual expectations and perception through digital alteration (in a completely different way) is Golan Levin.

Golan Levin - Augmented Hands

(http://www.flong.com/projects/augmented-hand-series/)

In his installation Augmented Hands, Levin uses a real-time software for people to use. The software captures people’s hands and projects distorted, impossible versions of their own hands which react in real time to their movement. This is a completely different approach to using digital tools to alter reality than the one Pfeiffer uses, however there are similarities. Both pieces address the issue of our reaction when our visual perception does not match our pre-constructed expectations. Pfeiffer’s work highlights our capacity to bridge that gap between reality and our digitally-altered perception of it, and making sense of a situation and event from its contextual cues only. Golan’s work, on the other hand (so punny!), pushes forward the awe and playfulness that this discrepancy between our perception and what we know to be real can yield to. One is somewhat closing the gap created by visual digital alteration between what we see and what we perceive by arguing that our pre-conditioned brains are a more important agents than our actual senses when it comes to our construct of reality. The other expands this gap by showing how challenging it is for our brains to process this discrepancy (maybe more so in this real time and self-reflective context), to see a realistic and responsive depiction of what we know to be false, and how we are drawn to exploring this failure at making sense of what we see.

LINKS

art21

http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/paul-pfeiffer

fragment of crucifixion video link

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cu12tN8AJdU

NYtimes article:

http://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/15/arts/art-in-review-paul-pfeiffer.html

Galleries

Paula Cooper Gallery, New YorkThe Project, New York